It was 1981 when Alan Zerobnick founded ShoeSchool. He wanted to create a comfortable environment where novice shoemakers could work together with professional crafters. In contrast to other educational organizations ShoeSchool managed to establish a warm atmosphere full of support. People worked daily and spent their evenings in the local cafes where they chatted and discussed their progress.

Alan Zerobnick

The whole shoe crafting process takes up to 5 days during which students complete several workshops. They produce shoes from scratch, nothing is pre-assembled. Together with Alan they think of the future footwear (anything from sandals to formal shoes) and identify the required materials and techniques, then sketch drafts. It is worth mentioning that there is no DIY kits, only raw materials, your own hands and step-by-step guidance by Alan.

The most important thing in custom shoe crafting is appropriate choice of a shoe last. Shoe last is a solid model of the foot and it is used for molding of the materials later on. The correct size of the shoe last will determine the comfort level of the output footwear. That’s why it is important to adjust the shoe last so that it exactly matches the foot. For this purpose Alan created his own software in the early 90s.

Alan calls himself “a retired 70 year old shoemaker with the passion to the technology”. His desire is to apply modern innovations to the ancient craft that has not been changing for hundreds of years. The software allowed to bring digital models of the shoe lasts to life by using lathe and milling machines. This means that people were forced to manually post-process the shoe last which is quite resource-intensive.

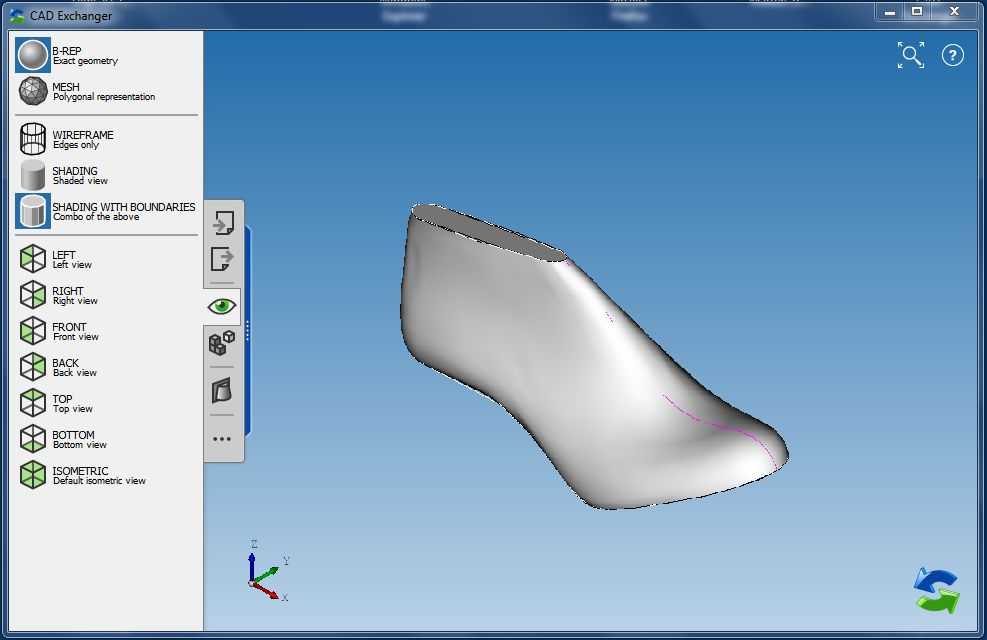

The massive spread of additive manufacturing and 3D printing technology revealed the next logical step – to print shoe lasts and thus shorten and simplify the production cycle. Sounds good. But there was a significant pitfall. The software Alan developed produced IGES files, which used NURBS (Non-Uniform Rational B-Spline) surfaces. This format is not suitable for 3D printing. It is a pretty common situation in the additive manufacturing industry. Modern 3D printers are able to process simple polygonal data such as STL and sometimes OBJ, VRML, Collada and other polygonal mesh formats. In case your CAD system fails to export such formats you will not be able to manufacture the model immediately. The conversion to STL, OBJ, or other polygonal format is needed.

The main challenge is tied with the IGES NURBS specifics. ‘The IGES - NURBS models used for converting the shoe lasts are Completely Amorphous Surfaces, comprised of compound curves, with no straight lines or flat surfaces.’- Alan says. Usually this is a headache in the context of conversion. The output STL or OBJ file might be slightly damaged and therefore fails to satisfy the criteria of waterproofness, which makes the whole model invalid for 3D printing.

CAD Exchanger successfully addresses those challenges with the help of the algorithms that process the IGES NURBS surfaces and heal the damaged edges and surfaces. It also validates the outcome to ensure its 3D printability. ‘It has been a journey of 18 years to find a conversion solution for my .iges files to .stl.’ –Alan claims. CAD Exchanger allowed to perform IGES to STL conversions and thus it’s now easy to design, produce and print the shoe lasts.

Today Alan still hosts educational classes and workshops aimed at the future generations of shoemakers. He is teaching students to design various types of footwear and leverage 3D printer and other modern technologies.

For more information this is a direct link to the ShoeSchool.com website.